Diaries from a Digitisation Project: the Never-Ending Effort of Language Digitisation.

Ladin is a language spoken by nearly 40.000 people who live scattered across five valleys, in a small section of the Italian Alps, the Dolomites. Like the other Romance languages (Italian, French, Spanish, etc.), it derives directly from Latin. It also presents influences from Raetic, the language of the people who lived in the oriental Alps before the Roman conquest, and from German, since German-speaking populations have been living north of the Ladin valleys since approximately the Late Middle Ages.

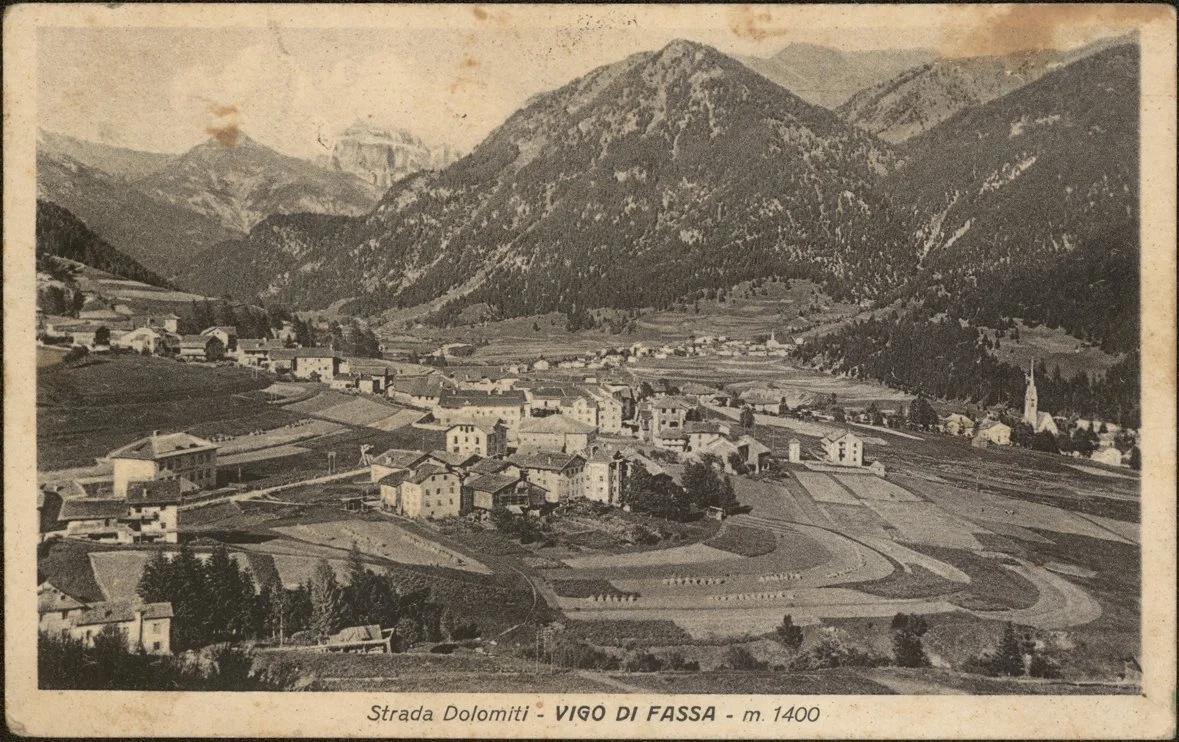

Strada Dolomiti - Vigo di Fassa - m. 1400 - 1945 - Digital Library Trentino, Italy - Public Domain.

The linguistic traits of the Rhaeto-Romance languages, those that distinguish Ladin from the other Romance languages, were once present in an area way vaster than the one where Ladin is spoken nowadays. The Germanic and Italian colonisation of the Alps, coming respectively from North and from South, spread these two languages to the detriment of Ladin, which remained spoken only in the higher, more remote valleys, where it still survives.

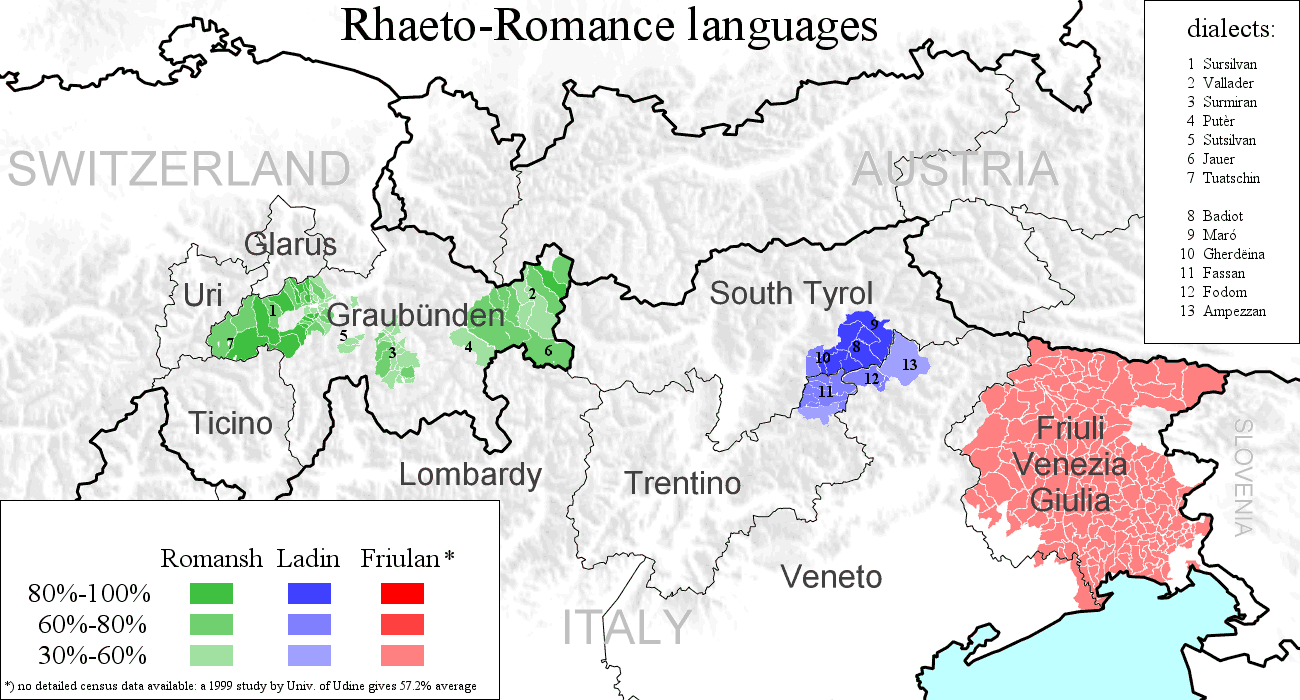

Sajoch, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

The three “linguistic islands” where Rhaeto-Romance languages are still spoken are the Grisons, Ladinia and Friuli. In the Early Middle Ages, the entire area that connects the three was inhabited by Rhaeto-Romanic-speaking communities.

Once the only language being spoken by the people living in these valleys, Ladin now lives side by side with German and Italian in its multilingual communities. Thanks to the struggles of Ladin activists of the last century, it is now the right of the Ladin people to use their mother tongue not only at home, but even in the public space and in institutional contexts, like at school or in public administration.

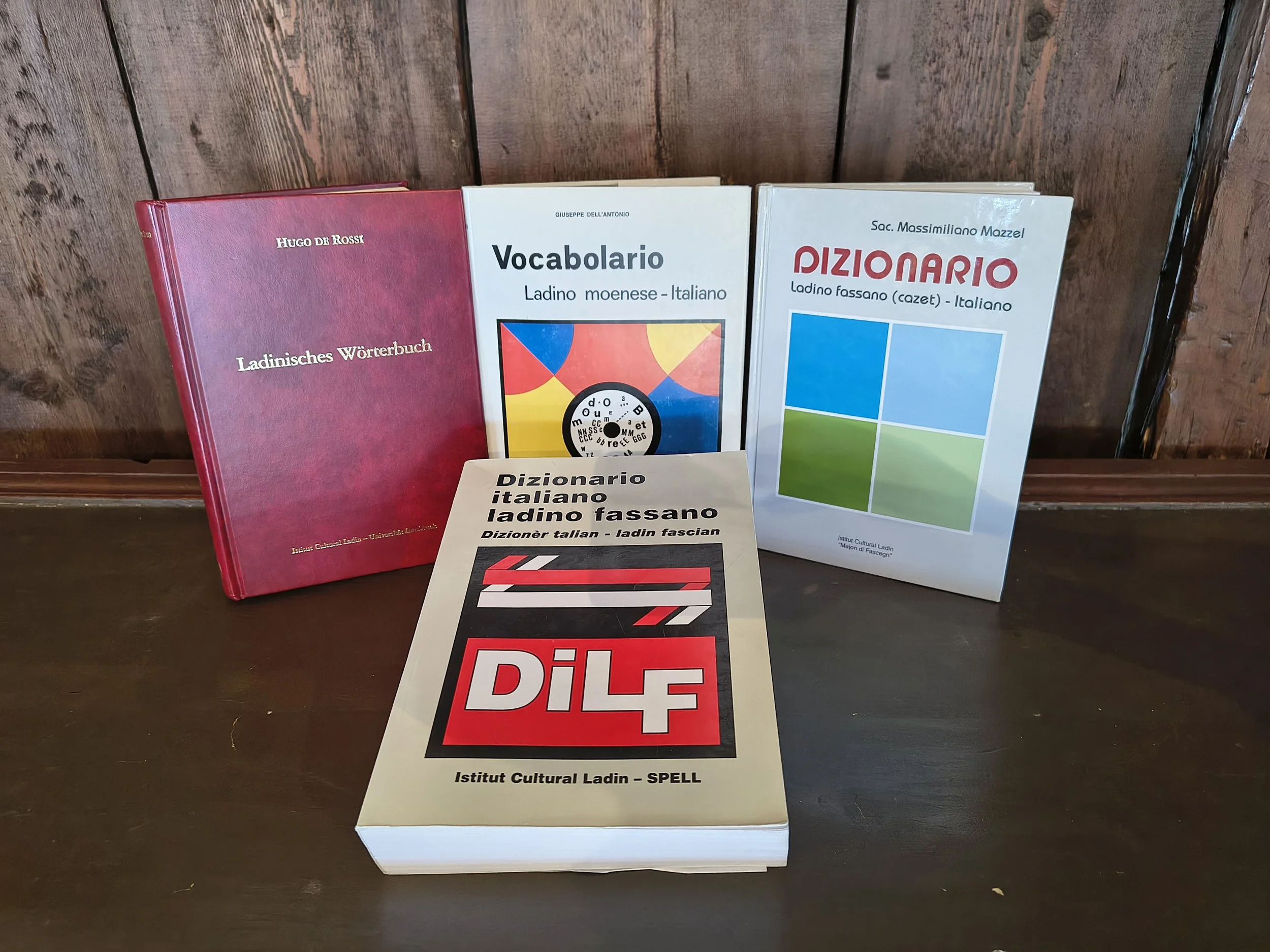

Like every language being used, Ladin needs its tools. The main one, alongside books and grammar manuals, is obviously the dictionary. Amateur language lovers had long been drafting dictionaries or word lists of the varieties of Ladin spoken in their village. Then, in the 1970s, the Istituto Culturale Ladin “majon di fascegn” was founded and became the reference point for everything grammar. It took the existing dictionaries and merged them into a single work, the DILF (Italian – Ladin of Fassa valley Dictionary), proposing an official model for the Ladin language, a standard.

The DILF alongside its predecessors, Sebastiano Dorich.

Lexicographic work is of particular importance for a language like Ladin. It, like every language, is ever-changing. But, given its minority nature inside the Italian state, it’s undergoing external pressures that hinder its natural evolution, in favour of a passive passage to foreign forms. The sudden and huge growth of the tourist economy of the second half of the twentieth century flooded the valleys with people from all over the world. The change in lifestyle and the intense contact with foreigners increased the presence of Italian and German in daily life, thus causing the partial loss of some Ladin expressions, words, traditions and knowledge. Documenting and regulating a minority language helps to make it able to endure the strong external influences of bigger, better-equipped national languages, allowing it to live on.

The DILF and the other lexicographic material compiled by the Istitut Cultural Ladin are currently undergoing a process of digitisation. The terms contained in the dictionary are being revised, enriched and then made available online. This will make the consultation easier and faster, stimulating the use of the dictionary. Allowing every speaker to take advantage of a richer array of linguistic possibilities will improve the quality of spoken and written Ladin.

However, you will say, how is it possible to digitise a language? A language is not an object; it has no defined boundaries, it is never present in its entirety, only in partial expressions of its potential, such as sentences, speeches, texts. How can you collect and store such an abstract entity?

And you would be right. The job of digitising a language is necessarily imperfect, incomplete; it’s a process of approximation, of an approach to an unachievable aim. Therefore, the lexicographer tries to better render the rich nature of language not by approaching their work as the compilation of a lifeless list of words, but by enhancing it with examples of the use of a word, samples of realistic speech, locutions, proverbs, photos or sketches when they can help to describe material culture, and so on.

People having a discussion during a livestock fair in the village of Moena, 1979, Istitut Cultural Ladin "majon di fascegn".

For the same reason, the task of digitising the culture that hides within a language must not be limited to pure lexicography. It must be combined with commitment to the documentation, study and digitisation of meaningful examples of the language in use – like texts or recordings of speech. These are the sources of our lexicographic work; they allow us to verify the fidelity towards real language in our descriptions of it and to observe it alive, being used for communicative means. For example, the Istitut Cultural Ladin “majon di fascegn” hosts on its website the “Mediateca Ladina”, a page where, among other things, you can listen to historical recordings of people speaking and narrating. Give it a listen! I think that, even if you do not understand Ladin, you will enjoy the cadence and the emphasis of the Ladin voice that gets documented there. Here you can find the address: https://mediateca.ladintal.it/oujes.page

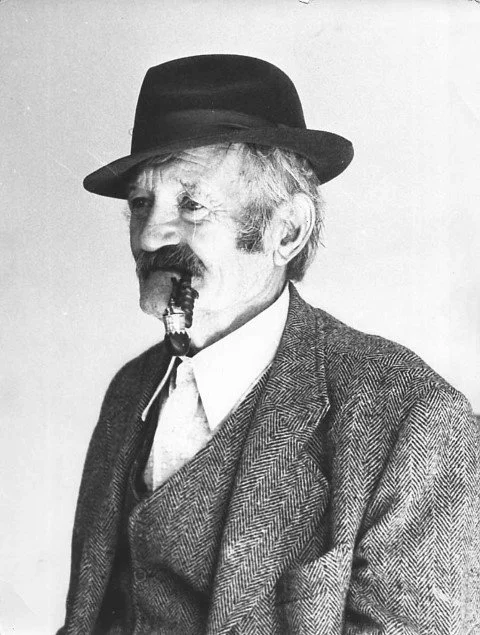

Giovanni Bernard de Cechinol, one of the people you can hear speak if you visit the Mediateca Ladina, Istitut Cultural Ladin "majon di fascegn".

Elisabetta Lis Salvador dal Vera, 1981, one of the people you can hear speak if you visit the Mediateca Ladina, Istitut Cultural Ladin "majon di fascegn".

And if you feel adventurous, at this address ( https://dilf.ladintal.it/ ), you can also explore the DILF, our ever-improving online dictionary of the Ladin of Fassa Valley!