Diaries from a Digitisation Project: Traditional Beekeeping in the Dolomites

The Ladin culture formed, over centuries, in a context of harsh material conditions. The people who lived in the valleys where Ladin is still spoken (in the Italian Alps, or more precisely, in the Dolomites) had to endure long and cold winters, to cultivate steep terrains with low sun exposure and live off the fruits of a climate and a land which were not generous in terms of quantity, nor in terms of variety.

Cereal fields in Fassa valley, 1925/1935, from the Amonn Archive owned by the Istitut Cultural Ladin "majon di fascegn"

The main occupations, which provided most of the essential goods, were to cultivate the fields located on the valley floor to grow barley, rye, potatoes, turnips and cabbage; to scythe the grass from the lowest to the highest fields and store it to feed cattle during winter; to graze and take care of cows and sheep; to cut and gather wood for heating and construction.

Then, in the 1950s and ’60s, the means of production and surviving for the Ladin communities changed, and the valleys converted, within a few decades, into a touristic economy.

A queue of skiers waiting for the skilift, 1960s, from the Guido Iori Rocia archive, owned by the Istitut Cultural Ladin "majon di fascegn"

The material foundation of the Ladin culture had been rapidly shaken and thus began a struggle to preserve it and pass it down. The pioneers of the documentation and the study of the traditional way of living of the Ladin people directed their attention especially towards the “cornerstones” of their culture: agriculture, hay harvest, livestock keeping.

People and goats on the mountain pasture. 1940/50s, owned by the Istitut Cultural Ladin "majon di fascegn"

However, life in the Ladin valleys was also full of minor traditions and activities, which, even today, decades after the beginning of the documentation processes, can be studied and addressed by the institutions that work in the field of cultural heritage. One of these is beekeeping.

A modern beekeeper in Fassa valley, 2023, picture taken by Davide Baldrati, and deposited in the Davide Baldrati archive by the Istitut Cultural Ladin "majon di fascegn"

The Istitut Cultural Ladin “majon di fascegn”, an institute that deals with Ladin culture in the Fassa Valley, is working, in the context of and with the help given by DIGICHer, to study the role and the practices of traditional beekeeping, gathering data with the participation of the community and digitalising it.

We started by asking. Personal connections are the easiest way to begin to gather information and the first form of involvement in the community, so we thought about our acquaintances, collected contacts and asked: did you or someone in your family keep bees? Who, in your village, was known for keeping bees? Can you bring me to this person, or ask if we can have a chat?

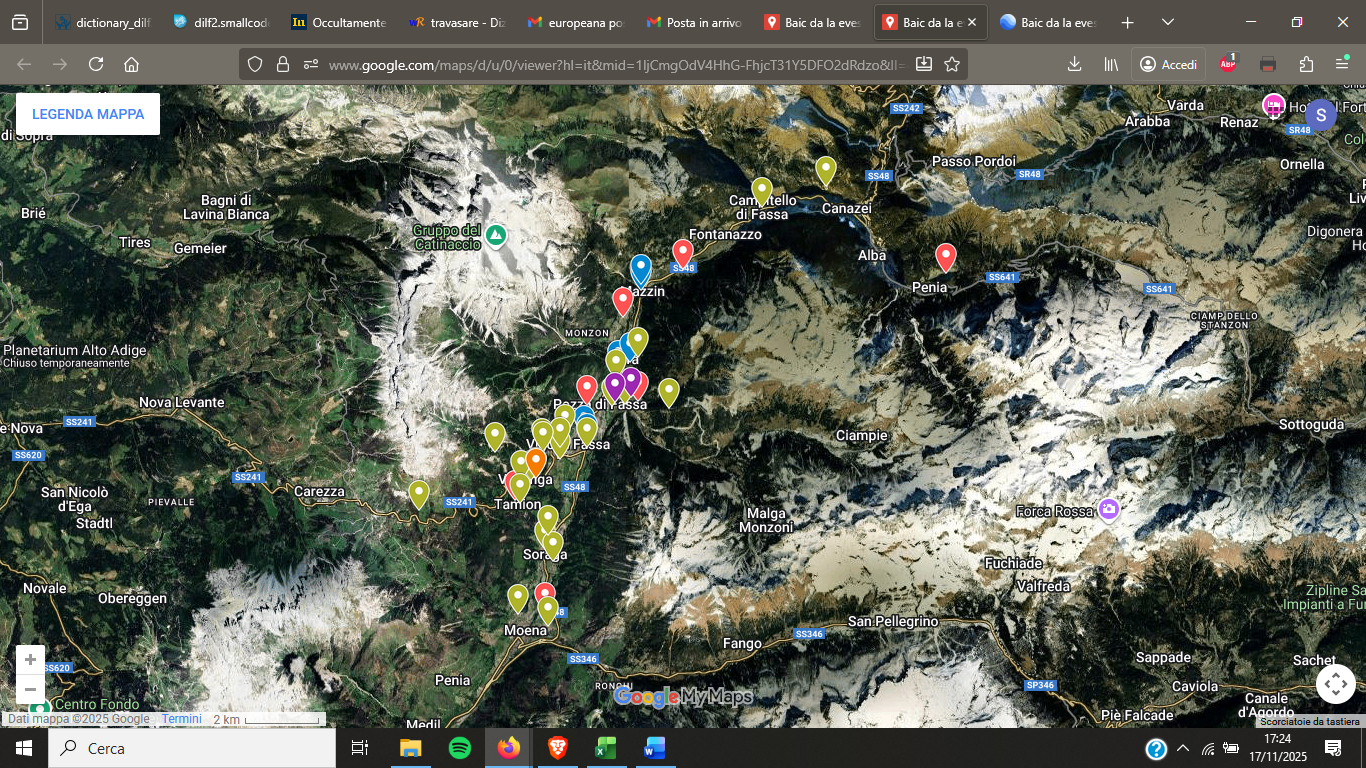

Reference after reference, the web spreads out from the first personal contacts, and the data becomes more systematic and thorough. In front of our eyes, a picture began to appear, made up of the people, places, objects, and practices of beekeeping. To make this picture more concrete, we put each one of these elements on a map.

Screenshot of the google service MyMaps

Each pin is a story, a person, an information, a place, an object related to our research. To map them is the first way in which we digitalise and store them. It also helps us to visualise the progression of our work, to notice at a glance where we must go to search for more, the villages where information is still missing.

The Istitut Cultural Ladin owns an ancient, beautiful apiary, which is now being restored and will host a section of the Museo Ladin, the ethnographic museum of the Ladin people. Therefore, we need materials and information to give a voice to the apiary.

The ancient apiary, 2020, Istitut Cultural Ladin "majon di fascegn"

Ornamental detail, 2020, Istitut Cultural Ladin "majon di fascegn"

In particular, we want to study how the people of the Fassa Valley kept bees in the past centuries, and which techniques and tools were used. We want to study the Ladin vocabulary of beekeeping. We want to know if ancient apiaries are still standing today (maybe used to store firewood or dusty knick-knacks), where they are and how they were used.

From what we are learning, we can understand that the practice of beekeeping in the Fassa Valley didn’t develop refined techniques, and didn’t develop into a real, advanced apiculture. It was more widespread than in-depth. For example, a large number of families had three or four hives, which were usually allowed to live and work freely. The intervention from humans was minimal and often limited to the collection of honey. In this way, with small effort, a family could obtain a few jars of honey every year. Honey wasn’t an essential food, but was for long the only sweetener available, and was also used against sore throats.

The “amateur” nature of beekeeping in the Fassa Valley is the reason for one of the main difficulties in our research: often, the members of the community disregard beekeeping as something secondary, of little interest. The backbone of our work is not only to gather and digitalise data, but first, to convince our participants that yes, we are, in fact, really interested in those half-broken tools that their grandpa used to employ, but then left in a corner of the cellar!

We almost missed one of the most interesting objects we found in our research, because the man we were interviewing found it of little interest! Luckily, and despite his initial puzzlement, we got to see and photograph this tool, a home press to fabricate the wax foundation given to the bees as a base to build honeycombs, something we have not seen from other participants.

In our visits to various people in the valley, we took pictures and recorded interviews, and later stored this data in digital formats. After the period of information gathering, we will stop and try to systematise what we’ve learnt, setting up the materials for the apiary-museum.

The digital and informatic tools we use to conduct our research are the best that the present puts at our disposal, because of their flexibility, their endurance, and their functionality. The treasure that we are collecting, cultural heritage, has nonetheless a “human” form: it is stored in the knowledge and memory of our people. We could thus say that the job of a researcher in the field of cultural heritage is to allow and optimise the transmission of human content in digital form.

Picture of a 19th century homepress, atraditional tool used to compact wax,

Istitut Cultural Ladin "majon di fascegn"